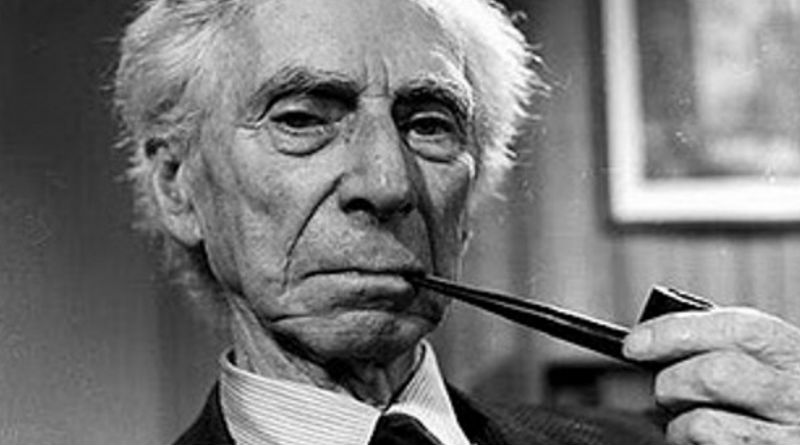

The Philosophy Of Bertrand Russell

Posted on November 2020

Bertrand Russell (1872 – 1970) was both a philosopher of science and a prominent peace campaigner.

Russell was born into a wealthy Welsh family and he studied mathematics at Cambridge University. He became an atheist, anti-war activist, and championed free trade between nations and anti-imperialism.

He was a prolific writer on many subjects (from his adolescent years, he wrote about 3,000 words a day, with relatively few corrections), and was a great popularizer of philosophy.

Philosophical Approach

Russell remained throughout his life, though, an out-and-out empiricist, in the tradition of Locke and Hume, and he always maintained that the scientific method was the best way to find answers.

“To teach how to live without certainty, and yet without being paralyzed by hesitation, is perhaps the chief thing that philosophy, in our age, can still do for those who study it.”

“My desire and wish is that the things I start with should be so obvious that you wonder why I spend my time stating them. This is what I aim at because the point of philosophy is to start with something so simple as not to seem worth stating, and to end with something so paradoxical that no one will believe it.”

Bertrand Russell

World War I & II

During World War I, Russell engaged in pacifist activities, which resulted in his dismissal from Cambridge following a conviction in 1916 and, in 1918, six months’ imprisonment in Brixton prison.

After the World War II, Russell moved to the United States, teaching at the University of Chicago and then the University of California, Los Angeles. He was appointed professor at the City College of New York in 1940, but the appointment was annulled by a court judgment after a public outcry over his opinions and morals.

He joined the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, lecturing to a varied audience on the history of philosophy. These lectures would form the basis of his book, A History of Western Philosophy (1945), a great commercial success that provided him with a steady income for the remainder of his life.

Russell returned to Britain in 1944 and rejoined Cambridge University. He was now world famous, even outside of academic circles, and also was frequently either the subject or author of magazine and newspaper articles – as well as a regular participant in many BBC radio broadcasts. In 1949, he was awarded the Order of Merit and, in 1950, the Nobel Prize for Literature.

The Russell–Einstein Manifesto

The Russell–Einstein Manifesto was issued in London on 9 July 1955 by Bertrand Russell in the midst of the Cold War. It highlighted the dangers posed by nuclear weapons and called for world leaders to seek peaceful resolutions to international conflict.

The signatories included eleven pre-eminent intellectuals and scientists, including Albert Einstein, who signed it just days before his death on 18 April 1955.

The manifesto, considered a key document in the beginnings of anti-nuclear campaigns, states:

“In view of the fact that in any future world war nuclear weapons will certainly be employed, and that such weapons threaten the continued existence of mankind, we urge the Governments of the world to realize, and to acknowledge publicly, that their purpose cannot be furthered by a world war, and we urge them, consequently, to find peaceful means for the settlement of all matters of dispute between them.”

Russell–Einstein Manifesto

Campaign For Nuclear Disarmament

In 1957, Russell was one of the founding members of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. To date, he is the peace organisation’s first and only president.

Committee Of 100 For Civil Disobedience Against Nuclear Warfare

In 1960, Russell also set up the Committee of 100 for Civil Disobedience against Nuclear Warfare. Russell was arrested and charged with inciting civil disobedience in 1961, ahead of expected mass civil disobedience in response to the arrival of the first US Polaris submarine in Scotland.

At the age of 89, he was jailed for his involvement in civil disobedience when protesting against nuclear weapons. His imprisonment raised the profile of the anti-nuclear movement enormously.

Freethinker

A champion of freedom of opinion and an opponent of both censorship and indoctrination, in 1957, Russell wrote:

“‘Free thought’ means thinking freely … to be worthy of the name freethinker he must be free of two things: the force of tradition and the tyranny of his own passions.”

Bertrand Russell

Russell died of influenza, in 1970, at his home in Wales. In accordance with his will, there was no religious ceremony but one minute’s silence. His ashes were scattered over the Welsh mountains later that year.

Image from www.jadaliyya.com